Why It Matters

Too often, the worlds of patient safety and maternal health are siloed, depriving both of valuable perspectives that could help prevent harm to all patients. Ebony Marcelle, CNM, MS, FACNM, Director of Midwifery at the Community of Hope Family Health and Birth Center in Washington, DC, has created a checklist that brings those worlds together, incorporating her maternal health expertise into a checklist that can be used in any setting and by any person who encounters a patient. In the following interview, Marcelle discusses the importance of challenging the status quo and why understanding the past is crucial to improving care now and in the future.

On how to design respectful care

The Maternal Health Equity Action Lab in Washington, DC, and the DC Primary Care Association put [the Respectful Care Team] together by inviting women from the community, community clinics, insurance companies, and managed care organizations. Some of our preliminary discussions were about why women were engaging in care. We realized that women who were not engaged in care often didn’t feel respected. Either they had a poor exchange or a horrible previous interaction with care that affected their decision-making going forward.

It’s complicated. When I talk about respectful care design, a lot of providers say, “What do you mean? Of course, I give [respectful] care.” We often don’t realize how the foundations of our education were laid and how they influence how we treat people. We don’t always value what women from the community are saying because we come from a training background that blames them when things go wrong. We say, “They didn’t make the right decisions. They didn’t do what they needed to do.” There are a lot of historical factors in this country that contribute to why people are where they are, from redlining to generational wealth gaps to education. If you haven’t faced all those barriers, they’re easy to ignore, but we can’t fix them until we have a broader conversation that includes that history.

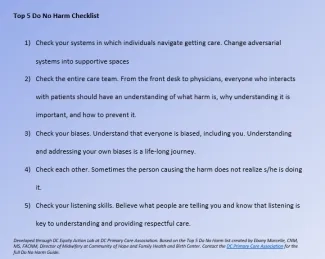

On the Do No Harm Checklist

Creating the checklist came from trying to answer the question of how to make something that’s not a 5,000-page document. The Equity Lab’s goal is to design something in 100 days. The Do No Harm Checklist came from me trying to condense what I could spend hours discussing into something that was quick, readable, and relatable.

The checklist is not just about obstetrics care. It’s for anybody who’s providing or supporting care, including the front office staff and nurses. It’s for whoever the patient is interacting with who needs to understand the role they play and the impact they can have on the [care] experience.

The Do No Harm Checklist gives providers an opportunity to reflect and think about how we’ve been trained in ways that sometimes result in not engaging well with patients. It gives us a chance to acknowledge how we’re functioning in systems that are not always treating patients well.

I understand there are going to be people who say, “There’s no way we can do all these things.” Why can’t we? Why can’t we make changes that we know could change outcomes?

On the importance of building on the research

Around the time we were starting to pull together the Respectful Care Team, Saraswathi Vedam and her collaborators published a great study [The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Measuring Respectful Maternity Care in the United States] that took a hard look at respectful care and listening to mothers. It was important that [our team] could say we were building [our work] on the data because some people don’t believe [there’s a problem] unless you have data.

Other research also supported listening to women. The DC Primary Care Association had a fellow, Robyn Russell, who published a 75-page report [called Human-Centered Solutions to Improve Reproductive and Maternal Health Outcomes in Washington, DC]. She interviewed providers, patients, and others. Both reports have been clear that women from the community should have a say in their care. What the research continues to document is that what women are saying is very powerful and often not taken into consideration. We realized we can’t design an intervention to fix things if we don’t involve the women.

On using the word “racism” and the limitations of implicit bias training

Racism is a lot bigger than one individual. Let’s move away from individual blame. Having all our providers do a two-hour class on implicit bias is not going to fix everything because racism and health disparities are systems issues.

I do some teaching at Georgetown University and helped create a new kind of learning for midwifery students that focused on racism and health disparities. And when I became a midwife, my thesis was about infant mortality among African Americans. I’ve often been in situations where I’ve had colleagues say, “You can’t use the word ‘racism.’” And I would say, “Really? Why?” There’s so much data that documents the existence of racism. But it can be a scary word to a lot of folks.

The father of modern obstetrics routinely performed surgery on slave women without anesthesia. A recent study found that about half of the medical students surveyed had false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites, including believing that black people had thicker skin and higher pain tolerance. Do we really think these are not connected? We need to have conversations about our ugly past in order to properly address what’s going on now.

We can’t sugarcoat this message anymore. When I think about the women in organizations who are out there doing this work — like Monica McLemore, Jessica Roach, Joia Crear-Perry, SisterSong — we are no longer afraid. We are no longer trying to package this into a nice petite message that doesn’t upset people because that’s not working.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity. The Maternal Health Equity Action Lab in Washington, DC, is part of the Better Maternal Outcomes: Redesigning Systems with Black Women initiative convened by IHI and funded by Merck for Mothers.

You may also be interested in: