Why It Matters

Photo by Mark Valentine | Unsplash

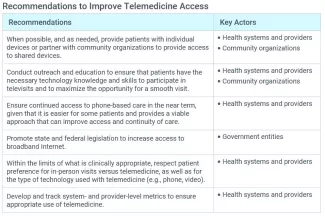

In 2020, telemedicine usage accelerated rapidly in much of the world because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Driven by an urgent need to keep patients safe from the virus while continuing to provide care, health care organizations rapidly scaled up telemedicine services. However, while infrastructure has rapidly expanded, it is important to recognize that a “digital divide” still exists in the US: Nearly one third of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband services, and the gap in access extends beyond rural America along economic and racial lines. The following is an excerpt from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Telemedicine: Ensuring Safe, Equitable, Person-Centered Virtual Care white paper that outlines recommendations for improving telemedicine access.

To take advantage of what telemedicine can offer, patients need to be able to access it. The most important considerations for patient access to telemedicine services include appropriate technological infrastructure (e.g., devices, internet connectivity) and basic technology knowledge and skills (sometimes referred to as digital literacy). It is also important to respect patient preference for the type of telemedicine technology they wish to use (e.g., telephone versus video).

The biggest barriers to telemedicine access involve infrastructure. About 15 percent of American households lack a smartphone and at least 10 percent lack access to the internet beyond cellular data. For video-based telemedicine visits, both the patient and provider need reliable access to the Internet or Wi-Fi signal and a device with video capabilities (e.g., laptop, smartphone, tablet).

Infrastructure and technological barriers differ by race, income, and geographic location, among other factors. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center study, African Americans were 12 percent less likely to have high-speed broadband access than whites, and only 74 percent of US adults living in households with annual incomes of less than $30,000 used the Internet versus 97 percent of adults in households with incomes greater than $75,000. For rural citizens in the US, almost 30 percent lack broadband access and 30 percent do not have a smartphone.

Government intervention can help increase access. For example, the US Federal Communications Commission’s COVID-19 Telehealth Pilot Program and Connected Care Pilot Program fund increased access to broadband and equipment for both patients and providers. Building the necessary infrastructure requires additional attention and resources from policymakers.

Improving telemedicine access requires the necessary infrastructure to meet the needs of the population. Pilot programs have demonstrated the feasibility of providing in-home equipment such as tablets, laptops, or devices connected to the TV to those who would otherwise lack access. Some health systems, such as Bellin Health in Wisconsin, have placed telemedicine kiosks in strategic locations, including schools and workplaces. Each kiosk includes a device, Internet connection, and access to ancillary equipment such as blood pressure cuffs and thermometers to facilitate the visit.

Another barrier to telemedicine access is an individual’s comfort level with technology and their technology knowledge and skills, which older adults disproportionately lack. In 2015, 58 percent of older adults in the US reported internet use, although that number continues to grow. A 2014 study found that older adults scored lower on measures of technological problem-solving than younger adults. Individuals with certain disabilities may face challenges with operating equipment.

At the same time, telemedicine offers clear opportunities for some of the very patients who may face the greatest barriers to access. Lower-income individuals may have more difficulty taking time off work, finding childcare, or accessing transportation to travel to a health care facility. Older patients and those with disabilities may face mobility constraints. Providers must address barriers as well as realize opportunities for using telemedicine to decrease, rather than increase, health inequities.

Health systems will need to conduct outreach and education to ensure that patients have the skills and familiarity with technology to participate in telemedicine if they so choose. Health systems and providers may also partner with community-based organizations to offer education and distribute relevant materials. Some health systems have already become more proactive about educating patients in advance of a televisit to ensure that they will be ready to engage. For example, prior to a virtual visit, a dermatology clinic in the Connecticut-based Yale New Haven Health System sends patients an electronic message with written instructions and a video tutorial on how to use the telemedicine services.

Not every patient will want to receive telemedicine services. Some may prefer telemedicine for certain types of appointments and not for others — and these preferences may not align with the expectations or preferences of providers. Some patients may prefer to interact with providers using the phone or email versus video. Older patients with less experience using technology, and patients who are uncomfortable with providers seeing into their home environments, may prefer phone rather than video appointments, for example. At every step, the guiding principle is to respect patient preference and autonomy, making an effort to provide access to telemedicine when it is desired and access to in-person visits or other services when those are more appropriate or preferred.

Incorporating patient preference is an important component of ensuring psychological safety. But what happens when patient and provider preferences are not aligned? Organizations need processes in place to support both patients and providers in making decisions about the most appropriate ways to deliver care, whether in person or virtual, and to coach providers on how to effectively communicate with patients around those decision points. Certain conditions also need to be in place (e.g., percentage of in-person vs. virtual visits, default to in-person visits for certain types of care or specific conditions) that support best practices established by the organization. It’s also important to collect and analyze data over time on patient outcomes and patient and provider satisfaction for both in-person and virtual care to assess effectiveness, safety, and quality in an ongoing way. Ultimately, telemedicine services need to be designed to both encourage patient preference and support clinical decision making.

To learn more — including additional recommendations for improving telemedicine download the free Telemedicine: Ensuring Safe, Equitable, Person-Centered Virtual Care white paper.

You may also be interested in: