Summary

- In improvement work, it’s important to understand the psychological factors that might be impeding change in addition to the technical ones. Combining Behavioral Insights (BI) with the Model for Improvement is one promising strategy.

Introduction and Context

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” This oft-quoted aphorism, attributed to George Box, highlights the challenge of using models to explain or explore highly complex situations. The challenge of improving health care delivery using models and tools is one such example. For more than 30 years, the focus in health care quality improvement (QI) has been to apply models adapted from industry and organizational management to address process, interaction, and system-related issues. However, there is a recognition that some of the recurring challenges in this field require greater attention to adaptive change — i.e., the human side of change.

The use of behavior change interventions as a means of improving outcomes for patients and service delivery has been shown to be a promising strategy. One such intervention is Behavioral Insights (BI), which refers to empirically tested knowledge from psychology, cognitive science, and social science about what shapes human behavior in predictable ways. As such, BI aims to understand factors that limit and promote behavior change and to use these insights to design effective change interventions.

For several years, we have been using the Associates in Process Improvement’s Model for Improvement to support change in health care settings. In addition, we both have an education in BI. The question we asked was, “What if models and tools from BI were applied to QI as a means of increasing our understanding of the psychological mechanisms involved in change?” The following is a brief introduction to some work we undertook at a hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Project Summary

At a 530-bed university hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark, the internal quality team had been invited by the clinical leads to facilitate a QI project focused on switching from intravenous (IV) antibiotics to oral antibiotics for acute care patients as soon as clinically appropriate. Research in this field highlights that prolonged use of IV antibiotics has been associated with catheter-related complications, longer length of hospital stays, increased treatment costs, and increased nurse time spent on administration. Nevertheless, prolonged use of IV antibiotics for acute patients was common at the hospital. The aim of the QI project was to reduce the average number of IV antibiotic days by 10 percent. Data were collected via the electronic clinical patient data system on all patients receiving at least one dose of IV antibiotics. Then these data were analyzed on a weekly basis, using statistical process control. Prolonged use of IV antibiotics is a result of clinical behaviors and choices, and therefore improvement requires behavior change. Our objective was to explore the possibility of using models and tools from BI to aid the understanding of the psychological mechanisms of change for clinical staff, and to use the insights to develop a BI-informed theory of change.

Core Findings

In an article published recently in the Journal of Patient Safety, we describe in detail the process we used to explore this question, the outcomes of the QI project, as well as some of the advantages and disadvantages of combining models from BI with models from QI. Below we aim to provide a flavor of the work by briefly outlining the BI model we used, some of the tools that aided our understanding of the psychological mechanisms for staff involved in the work, and examples of the kinds of barriers we identified and the interventions we tested.

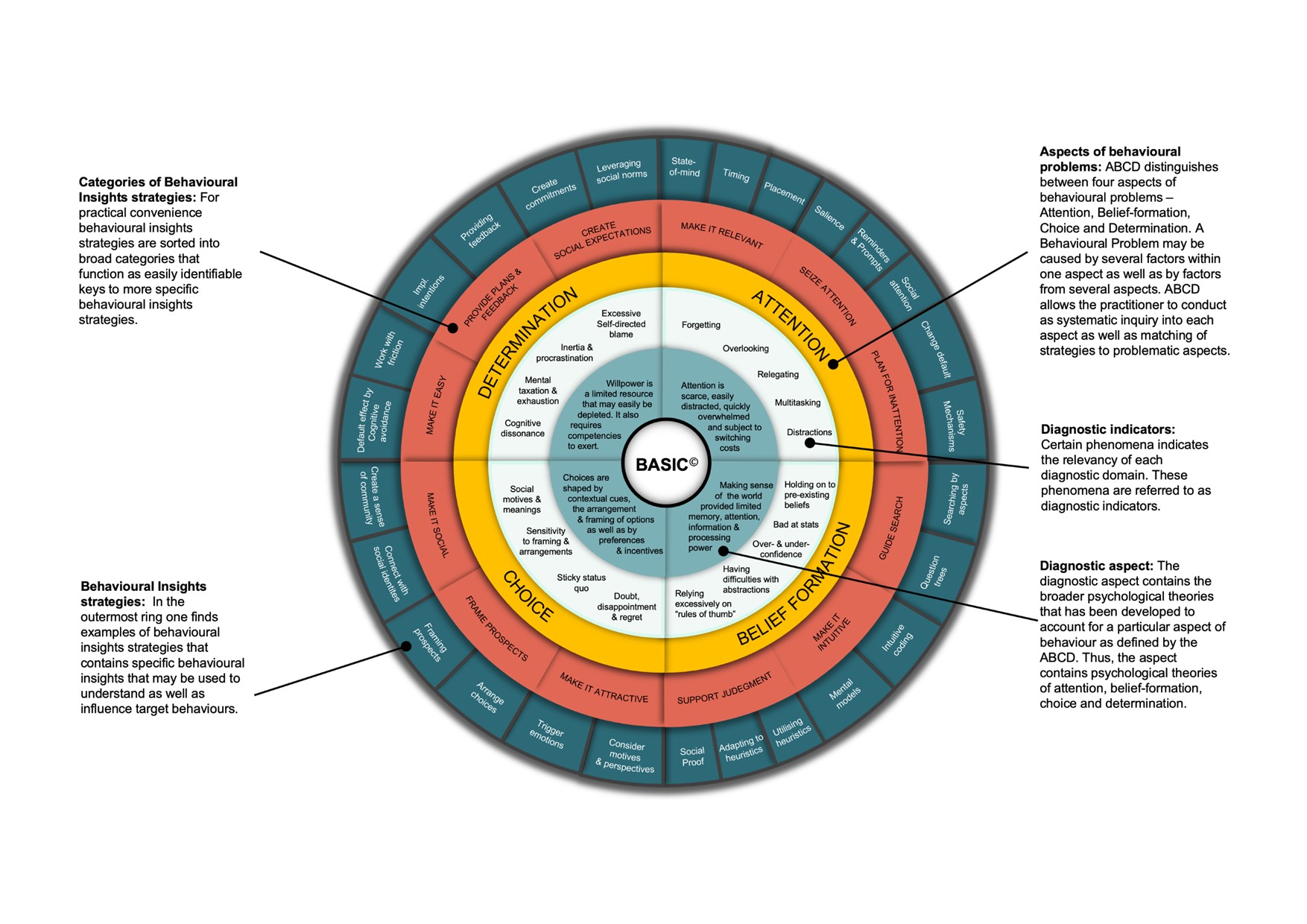

We used the BASIC model, developed by Pelle Guldborg Hansen and used by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The model provides guidance on how to apply BI, and the name is a mnemonic of the different stages in the process of developing effective BI interventions: Behavior, Analysis, Strategy, Intervention, and Change. A key component of the analysis process is the ABCD wheel, which represents four aspects of behavior that cause deviations from the targeted behavior: Attention, Belief formation, Choice, and Determination (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. ABCD wheel. The ABCD wheel focuses on four key drivers of behavioral problems: attention, belief formation, choice, and determination and the corresponding strategies for change. Reprinted with permission from Pelle Guldborg Hansen.

The ABCD wheel is a diagnostic tool that can be used to identify the psychological mechanisms involved in any given process and help match the corresponding behaviorally informed change strategies. The wheel can help answer the question of why some interventions work and others don’t. These characteristics make it particularly useful for integration into QI.

Another key tool taken from BASIC was the use of behavior flow charts to identify actions and procedures involved in the antibiotic decision-making process. The flow chart is developed via observation, interviews, and feedback from staff involved in the process. A strength of this tool is the potential to identify decision-making opportunities, as well as barriers or facilitators toward the desired behavior (i.e., switching the route of antibiotics).

As a result of using these tools, we were able to identify key moments in the clinical process where decisions about antibiotics could or should be made. We also identified the barriers to decision making and appropriate evidence-based interventions to overcome them. For example, “default” and “mental inertia” were identified as barriers to switching in the behavior flow chart. We know from BI that willpower is a limited resource. As a result, in highly complex situations, with large amounts of information to be processed under time pressure, willpower depletion will typically result in sticking with the default. In acute care settings, IV antibiotics are the default option. Accordingly, the evidence suggests that making the decision process easy, providing plans and feedback, and creating social expectations will support behavior change.

These interventions constitute broad change ideas, which can subsequently be tested via plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles. In our project, to support clinical decision making when faced with “default” and “mental inertia,” we tested two change ideas. First, the clinicians were provided with a pocket guide containing an easy-to-use decision tree outlining when and for whom switching is appropriate. Second, changes were made to the electronic health record to include visual markers and information highlighting the possibility of switching from IV to oral.

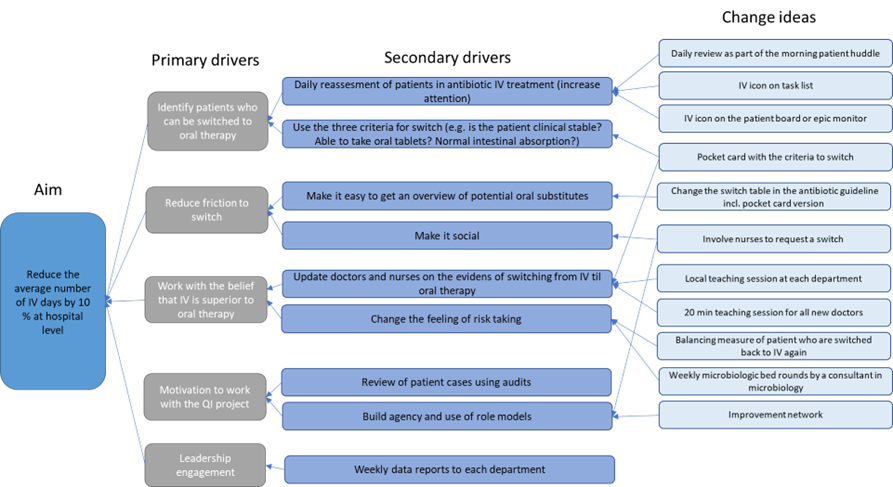

As you can see from the driver diagram below, multiple barriers were identified and interventions tested.

Figure 2. Driver diagram including BI factors.

Conclusion

The project achieved its aim of reducing the average number of IV days by 10 percent. Crucially, the reduction was also maintained beyond the lifespan of the QI project. Although this is just a single example, we found that using this systematic approach to identifying, diagnosing, and intervening provided a compelling addition to current improvement methods specific to the behavioral aspects of change.

Furthermore, the use of BI may also help address the challenge in QI around scientific rigor and the recognition that there is a great deal of uncertainty about which methods work and under which conditions. The application of the analysis and intervention strategies derived from the ABCD wheel may provide clarity regarding the psychological mechanisms underpinning a successful change process, which would aid replicability and spread.

Many more details, plus our reflections about the possible advantages and disadvantages of combining BI with QI, are explored in the article. We would be keen to hear from others who may be interested in adopting a similar approach (or already have) so that we can build a body of experience and knowledge around this important aspect of improvement work.

Rie Johansen is a Special Consultant, Department of Quality and Education, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg University Hospital, Copenhagen.

Simon Tulloch is a psychologist and Senior Advisor at the Danish Society for Patient Safety, Copenhagen.

Photo credit: melitas