Model for Improvement question: What change can we make that will result in improvement?

While all changes do not lead to improvement, all improvement requires change. The ability to develop, test, and implement changes is essential for an individual, group, or organization that wants to improve.

System-level improvement usually requires fundamental changes to the design of the system that result in improved performance and outcomes without increasing costs — not just quick fixes to bring a system back into control or to a previous level of performance.

To answer the third question in the Model for Improvement — What change can we make that will result in improvement? —the following might be helpful:

- Careful examination of the existing system (using flowcharts, for example)

- Exploration of the current system attributes that get in the way of better performance (a cause and effect diagram might be useful)

- Investigation of best practices inside and outside your organization to understand what is possible

When generating ideas for change that will result in improvement, subject matter expertise is valuable. Ideas may come from the literature, point-of-care staff, customers of the system being improved, researchers, and other experts, and should be adapted for the local context. Developing a theory (or conceptual model sometimes represented in a driver diagram, for example) that organizes and describes how the changes will result in improvement in the system is a key part of getting started.

Another useful set of tools for identifying changes are “change concepts” — general notions or approaches to change that have been found to be useful in developing specific ideas for changes that lead to improvement. Creatively combining these change concepts with knowledge about specific subjects can help generate ideas for tests of change.

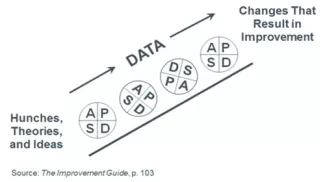

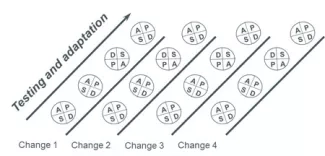

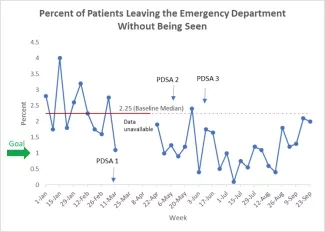

Wherever you find your ideas for change, run Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to test a change or group of changes on a small scale to learn how they work in your local environment and see if they result in improvement. If they do, expand the tests and gradually incorporate larger samples and under a variety of conditions until you are confident that the changes can and should be implemented and adopted more widely.

The change concepts included here were developed by Associates in Process Improvement (see The Improvement Guide [Langley GJ, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, Inc.; 2009] for a list of 72 change concepts, as well as examples of how they were applied in process improvement, both inside and outside of health care).

Examples of Categories of Change Concepts

Eliminate Waste

In a broad sense, waste can be considered as any activity or resource in an organization that does not add value to an external customer. Some possible examples of waste are materials that are thrown away, rework of materials and documents, movement of items from one place to another, inventories, time spent waiting in line, people working in processes that are not important to the customer, extra steps or motion in a process, repeating work that has previously been done by others, over-specification of materials and requirements, and more staff than required to match the demand for products and services.

Toyota is famous for focusing improvement on the following "seven wastes":

- Waste of overproduction

- Waste of waiting

- Waste of transportation

- Waste of processing itself

- Waste of inventory (stock)

- Waste of motion

- Waste of producing defective parts or products

Improve Workflow

Products and services are produced by processes. How does work flow in these processes? What is the plan to get work through a process? Are the various steps in the process arranged and prioritized to obtain quality outcomes at low costs? How can we change the workflow so that the process is less reactive and more planned? A flowchart is a great tool for understanding your existing processes and envisioning improvement in workflow.

Optimize Inventory

Inventory of all types is a possible source of waste in organizations. Inventory requires capital investment, storage space, and people to handle and keep track of it. In manufacturing organizations, inventory includes raw material waiting to be processed, in-process inventory, and finished goods inventory. For service organizations, the number of skilled workers available is often the key inventory issue. Extra inventory can result in higher costs with no improvement in performance for an organization. How can we reduce costs associated with the maintenance of inventory? Understanding where inventory is stored in a system is the first step in finding opportunities for improvement.

The use of inventory pull systems such as "just-in-time" is one philosophy of operating an organization to minimize the waste from inventory. In a pull system of service, the timely transition of work from one step in the process to another is the primary responsibility of the downstream (i.e., subsequent) process. This is in contrast to most traditional push systems, in which the transition of work is the responsibility of the upstream (i.e., prior) process.

Change the Work Environment

What would make the environment better able to support improvement? Examples of change concepts to change the work environment include the following:

- Invest more resources in improvement

- Give people access to information

- Conduct training

- Implement cross-training

- Develop alliances and cooperative relationships

Producer/Customer Interface

To benefit from improvements in quality of products and services, the customer must recognize and appreciate the improvements. Many ideas for improvement can come directly from a supplier or from the producer's customers. Many problems in organizations occur because the producer does not understand the important aspects of the customers’ needs or customers are not clear about their expectations from suppliers. The interface between producer/provider and their customers presents opportunities to learn and develop changes that will lead to improvement.

Manage Time

This age-old concept provides an opportunity to make time a focal point for improving any organization. An organization can gain a competitive advantage by reducing the time to develop new products, waiting times for services, lead times for orders and deliveries, and cycle times for all functions in the organization. Many organizations have estimated that less than five percent of the time needed to manufacture and deliver a product to a customer is actually dedicated to producing the product. The rest of the time is spent starting up or waiting.

Focus on Variation

Everything varies! But how does knowing this help us to develop changes that will lead to improvement? Many quality and cost problems in a process or product are due to variation. The same process that produces 95 percent on-time delivery or good product is the same process that produces the other 5 percent of late deliveries or bad product. Reduction of variation in such cases will improve the predictability of outcomes (may actually exceed customer expectations) and help to reduce the frequency of poor results.

Error Proofing

Errors occur when our actions do not agree with our intentions even though we are capable of carrying out the task. Often, we have to act quickly in a given situation or are required to accomplish a number of tasks sequentially or even simultaneously. Making these slips is part of being human. We might do such things as:

- Forget to enter information or enter it incorrectly

- Leave out a step in a process or do them in the wrong sequence

- Include the wrong merchandise in a shipment

- Try to use something in the wrong way

- Put something together wrong

Although these errors or slips are the result of human actions, they occur because of the interaction of people with a system. Some systems are more prone to error than others. We can reduce errors by redesigning the system to make it less likely for people in the system to make errors. This type of system design or redesign is called error proofing.

Focus on the Product or Service

What improvements can you make to the design of the product or service? Examples of change concepts that focus on the product or service include the following:

- Mass customize

- Reduce the number of components

- Change the order of process steps

- Differentiate using quality dimensions